Working with coroutines is subtly different from normal locking functions. Introduce some thread-safety with mutex.

Thread-Safety, normally

So hopefully you’re aware of basic thread-safety in Kotlin/Java. Sometimes you have a shared state of some kind that should only be accessed by one thread at a time. If you’re coming from Java, you probably use the synchronized(lock) operator in order to ensure that a shared mutable object can only be accessed one at a time. For some great reading on this topic I suggest this post on Medium.

So imagine a scenario where we are running a few long-running operations (like API calls), but we want to make sure that we never run more than one such operation at a time.

When I was starting out with Java threading I’d probably write something risky like this:

import kotlinx.coroutines.GlobalScope

import kotlinx.coroutines.launch

fun main() {

val lockClass = SyncLockClass()

for (i in 1..10) {

GlobalScope.launch { lockClass.runFunction(i) }

}

Thread.sleep(2000) // We're sleeping here because otherwise the JVM would terminate before printing the results

}

class SyncLockClass() {

val lock = Any()

var latestValue: Int = 0

//sampleStart

fun runFunction(input: Int) {

println("start function $input")

[mark]synchronized(lock) {[/mark]

Thread.sleep(100) // This could also be a long-running calculation or an API call

latestValue = input

}

println("finished function $input at ${System.currentTimeMillis()}")

}

//sampleEnd

companion object {

// Put the sync lock inside a companion object if you want to ensure that all instances of this class share a lock

// val lock = Any()

}

}

Press the play button above (assuming you didn’t block JavaScript on this page) to see the result. Each function is blocked and waits at the synchronized keyword for the previous function to finish. This mostly satisfies our initial requirement, but blocks any thread which hits the synchronized section while it is locked. Notice how once the first few functions are hit, the JVM is blocked from starting new threads until the previous thread finishes. In other words this method works (but is dangerous) if you have lots of threads and are running blocking functions. In Kotlin Coroutines however we run suspending functions, not blocking functions.

Badly, with Coroutines

If you’re already using coroutines you should know that a suspending function does not always block a thread. In some circumstances it pauses (suspends) the operation so that other operations can use the CPU.

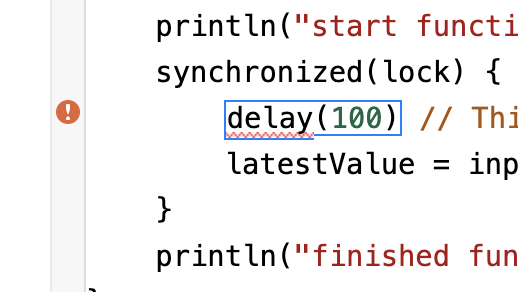

In the example above, I’m using coroutines to launch the function, but I’m still blocking the thread every time the runFunction() function is performed, which means I’m not really utilizing the full power of Kotlin coroutines. So, what if we replaced the blocking Sleep function with the suspending delay() function?

import kotlinx.coroutines.GlobalScope

import kotlinx.coroutines.launch

import kotlinx.coroutines.delay

fun main() {

val lockClass = SyncLockClass()

for (i in 1..10) {

GlobalScope.launch { lockClass.runFunction(i) }

}

Thread.sleep(2000) // We're sleeping here because otherwise the JVM would terminate before printing the results

}

class SyncLockClass() {

val lock = Any()

var latestValue: Int = 0

//sampleStart

suspend fun runFunction(input: Int) {

println("start function $input")

synchronized(lock) {

[mark]delay(100)[/mark] // This could also be a long-running calculation or an API call

latestValue = input

}

println("finished function $input at ${System.currentTimeMillis()}")

}

//sampleEnd

}

Try to run the above code and you’ll get an error: The 'delay' suspension point is inside a critical section. What does this mean? You should not delay or suspend or sleep your thread inside of a synchronized() block, as explained somewhat in this StackOverflow Thread. It would ideally display as a warning in my first example as well. A critical section of code (such as in between the synchronized block) should be as short as possible. It is not for long-running operations because it blocks the thread. But a suspending function does not necessarily block the thread.

So how do we solve this issue? Maybe you’re an oldschool Java dev and you think to just use ReentrantLock() instead. After all, synchronized is merely a simplified version of ReentrantLock. This is cheating to try and be smarter than the compiler. Don’t do this. Run the code below to see why.

import kotlinx.coroutines.GlobalScope

import kotlinx.coroutines.launch

import kotlinx.coroutines.delay

import java.util.concurrent.locks.ReentrantLock

fun main() {

val lockClass = SyncLockClass()

for (i in 1..10) {

GlobalScope.launch { lockClass.runFunction(i) }

}

Thread.sleep(2000) // We're sleeping here because otherwise the JVM would terminate before printing the results

}

class SyncLockClass() {

val reentrantLock = ReentrantLock()

var latestValue: Int = 0

//sampleStart

suspend fun runFunction(input: Int) {

println("start function $input")

reentrantLock.lock()

[mark]delay(100)[/mark] // This could also be a long-running calculation or an API call

latestValue = input

reentrantLock.unlock()

println("finished function $input at ${System.currentTimeMillis()}")

}

//sampleEnd

}

As you can see this is not the results we want at all. The lock breaks, and then it gets ignored. You’ll probably have a runtime error in the log as well. So how do we fix this? We use a Mutex.

Coroutines.Sync.Mutex

There are some things we can read online on Mutex. We’ve got the class documentation, we have this nice acricte which explains how to use the mutex with a shared mutable state, and finally we have the official kotlin guide. That last link is probably the best one.

The important takeaway is that the Mutex is part of the Coroutines package, which means we know that this mutex takes the suspending nature of coroutines into account. So how would we use it in our example?

import kotlinx.coroutines.GlobalScope

import kotlinx.coroutines.launch

import kotlinx.coroutines.delay

import kotlinx.coroutines.sync.Mutex

import kotlinx.coroutines.sync.withLock

fun main() {

val lockClass = SyncLockClass()

for (i in 1..10) {

GlobalScope.launch { lockClass.runSuspendFunctionWithMutex(i) }

}

Thread.sleep(2000) // We're sleeping here because otherwise the JVM would terminate before printing the results

}

class SyncLockClass() {

var latestValue: Int = 0

val mutex = Mutex()

//sampleStart

suspend fun runSuspendFunctionWithMutex(input: Int) {

println("running suspend function $input")

[mark]mutex.withLock { [/mark]

delay(100) // This could also be a long-running calculation or an API call

println("finished suspend function $input at ${System.currentTimeMillis()}")

latestValue = input

}

}

//sampleEnd

}

And now things are working fine. All of the API calls are started as soon as possible and none of the threads are locked. If you look at the timestamps of the logs above you’ll see that the events are also returned with the expected 100ms delay in between each one. The only way to have achieved this result using the same techniques as in the first example is to have 10 threads at your disposal. In fact, I can probably increase the amount of coroutines I launch with this method. Let’s push it until we break it:

import kotlinx.coroutines.GlobalScope

import kotlinx.coroutines.launch

import kotlinx.coroutines.delay

import kotlinx.coroutines.sync.Mutex

import kotlinx.coroutines.sync.withLock

fun main() {

val lockClass = SyncLockClass()

println("(only printing the first 3, and multiples of 50)")

//sampleStart

for (i in 1..4000) {

GlobalScope.launch { lockClass.runSuspendFunctionWithMutex(i) }

}

Thread.sleep(8000) // We're sleeping here because otherwise the JVM would terminate before printing the results

//sampleEnd

}

class SyncLockClass() {

var latestValue: Int = 0

val mutex = Mutex()

suspend fun runSuspendFunctionWithMutex(input: Int) {

if (input < 4 || input % 50 == 0)

println("running suspend function $input")

mutex.withLock {

delay(2) // This could also be a long-running calculation or an API call

if (input < 4 || input % 50 == 0)

println("finished suspend function $input at ${System.currentTimeMillis()}")

latestValue = input

}

}

}

I didn’t manage to break the Kotlin Playground with any amount of coroutines. The environment provided by the Kotlin playground only allows you to run for 10 seconds. The above code maximises that time without breaking anything, or blocking any threads. If you scroll through the logs you’ll see that some of the old functions are eventually getting finished while more coroutines are still being launched. This just goes to show how powerful coroutines and suspending functions are.

A Better way?

Threading and concurrency is a difficult topic. It is exceptionally easy to shoot yourself in the foot, by for example creating a deadlock. I suggest you read this great article by Roman Elizarov on how to avoid deadlocks in practical coroutines. (Thanks to Johannes Jensen for the suggestion.)

Our code sample above works, but it’s still dangerous. If one function gets locked or indefinitely suspended for any reason, you end up in a deadlock. Ideally you want to avoid launching a coroutine or entering a suspend function until the conditions are ideal to do so. If you cannot stop a coroutine from being launched when it’s not ready, you can at least queue up several suspend functions using the Mutex class.

But since we’re queuing things up, maybe it would be better to use something like the BlockingQueue class in Java? I’m still investigating that part, but spoilers: Channels

Conclusion

Coroutines are better than multithreading, but comes with all of the same dangers as normal multithreading. Just because it’s easy to use does not mean it’s safe. Be careful out there.

Can you think of a better way to handle this scenario? Please let me know in the comments below.