Kotlin allows us to structure our code around compile-time tests. This post explains how.

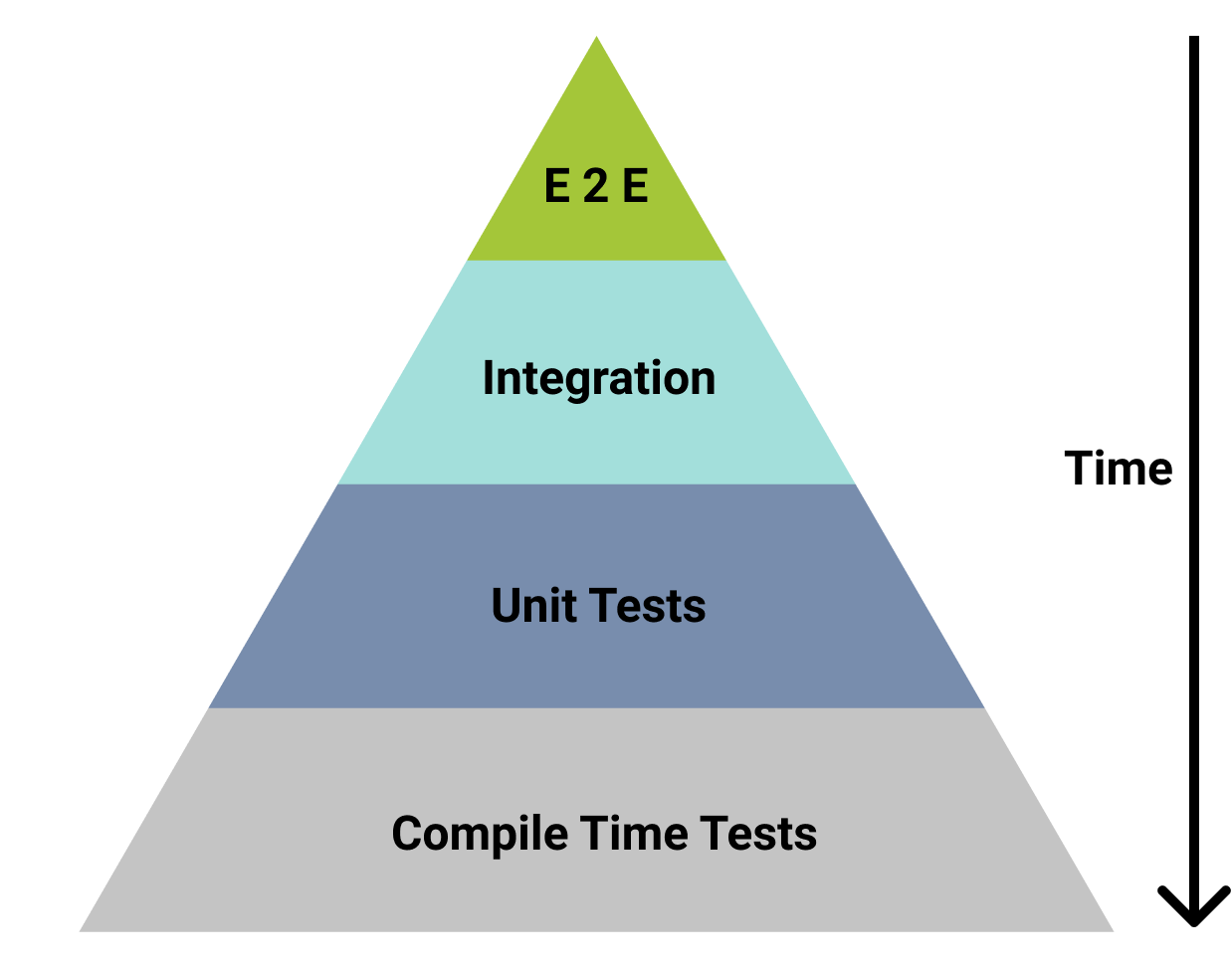

Four layered testing pyramid

You probably know the testing pyramid. Unit tests run faster and are easier to develop and run, so you should have more of them, compared to your integration tests and end-to-end tests. However if you assume that this pyramid applies to any sort of automated validation of your code, then the testing pyramid should actually look like this:

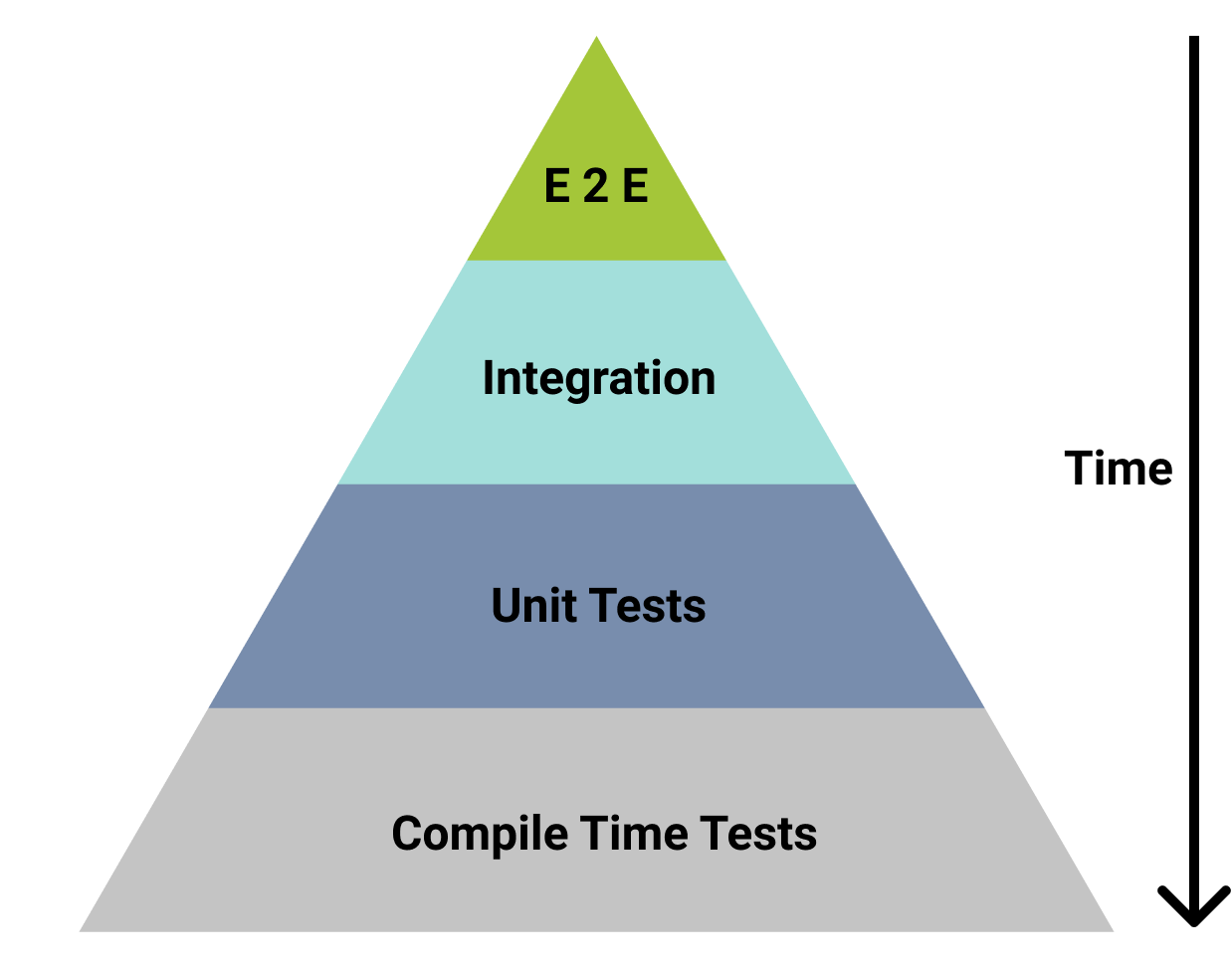

Testing Pyramid+

If you’re wondering what Compile Time tests mean, I mean everything that runs during and even before compilation, to provide “Compile Time Safety”: Static Analysis, Syntax Errors, Linting, Generated Classes, (Gradle) Build Tool Tasks and anything else I might be forgetting. Compile time tests refers to any errors you get that prevent your unit-tests from running in the first place.

I’m sure I’m not the first one to propose this. I looked around and found a few other similar ideas, but only really in the JavaScript community. My guess is that since they cannot rely on the compiler by default, they consider the addition of static tests to be part of the testing framework. Java/Kotlin developers, on the other hand, consider type safety to be an assumed but separate step from the testing framework.

Fail Fast Verification

Leaving the pyramid aside, I knew that the concept had to be much older than 2016. I did some research and found this amazing paper by Margaret Hamilton. If you don’t know Margaret Hamilton, all you have to know is that she’s able to ship bug-free code, like some kind of mad scientist. You need to read the full article, but for our purposes I’ll sum up the relevant parts. Her proposal is that a software system should be verified in this order:

- Conceptually

- Statically

- Dynamically

The static verification at the time was extremely limited, so they had to build a lot of it themselves. Margaret Hamilton took “fail fast” to its logical conclusion and did everything in her power to pick up problems before they became problems; first in planning, then in code. She also designed and implemented end-to-end testing systems, but preferred to have the majority of the validation be done before the end-to-end tests ran. Furthermore, her analyses concluded that bugs are less likely to occur if you have modular systems, as well as extensive documentation, specifications and conceptual planning in place before coding starts.

So with that background in place, let’s get back to the four-layered testing pyramid.

Four layered testing pyramid, in Kotlin

Testing Pyramid+

You should be aware that there are some variations to and criticism of the original testing pyramid, but that it makes a good rule of thumb for architecting your processes and systems. When you search for blogs or literature about how the testing pyramid fits into software development, you will find little-to-zero mention of static analysis or compiler checks. Yet if you’re coding in Java/Kotlin your IDE is constantly running automated checks on your code that most people consider to be completely separate from their automated tests. It is important to consider compile-time tests as just one part of a bigger system of automated software validation.

Considering that every function is tested for spelling and reference, for number of arguments, for return type, and various other checks by the compiler, I think it is fair to say that the number of verifications performed by the compiler exceeds those performed by your unit-tests.

The Implication On Your Daily Process

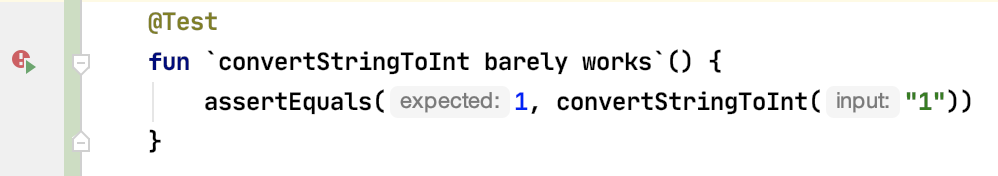

Test-Driven-Development is meant to teach you to architect your code in such a way that makes it easy to test. First you write a failing test, then you make that test pass. The first step, according to TDD, is to have a failing test that looks something like this:

First Failing Test?

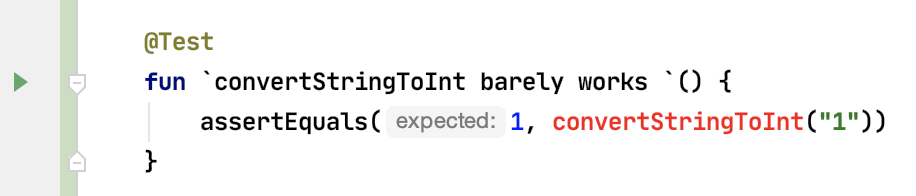

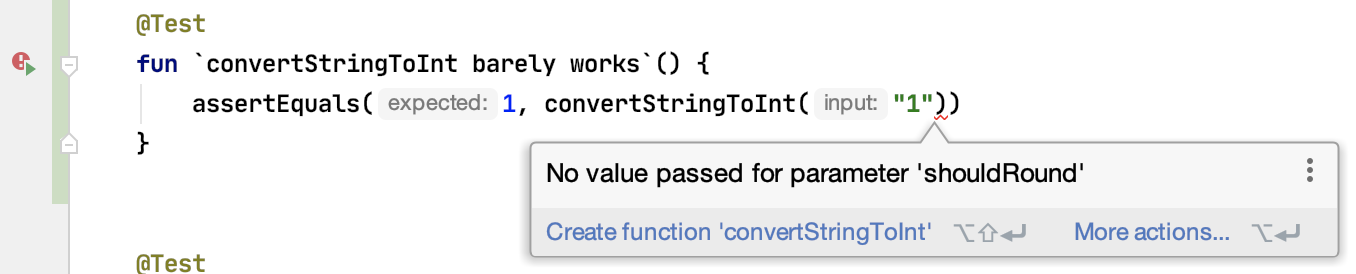

But I see this as the first failing test:

First Failing Test

This seems like a dumb distinction to make, but I believe it to be important. If you change the type of input or the number of arguments for the convertStringToInt function, your tests don’t fail; the compilation fails before your tests can even run. Which means the input-type and input-amount test is performed automatically, but that it is still a verification step that fails properly.

The Implications On Your Architecture

Not everyone uses TDD, but everyone should architect their Android projects in such a way that it is easy to unit-test. By going down this route you will hopefully start to implement some of the popular and sensible choices:

- Modularization

- Inversion of Control via Dependency Injection

- Decoupling Classes / Dependencies

- Functional Reactive Programming

- Pretty much everything written in Refactoring by Fowler

And various other small techniques that you develop subconsciously as you prioritise around testability.

However, what if you prioritise your architecture to go beyond failing fast in unit tests? What if you prioritise things to fail fast like in the 4-layered test-pyramid above? Breaking changes should ideally fail at compile-time. For me, as an Android Developer, this is the ideal. My compile-time is often around a full minute and I’d prefer if breaking changes alerted me before I even have to do a full compile, much less run tests.

A simple example would be if my convertStringToInt function required an additional argument. I’d get this error:

Perfect test: it failed before it even ran

If you want to pick up breaking changes faster, your goal is to structure your code in a way where breaking changes more often cause compile time errors before they cause test failures.

“Okay, cool. Compilation errors are sometimes better than test failures. So give me some practical examples”

This was the theoretical portion. In the follow-ups to this post, I’ll give some practical examples, which may include: This was the theoretical portion. In the follow-ups to this post, I’ll give some practical examples, which may include:

- Using named arguments

- //TODO: Using custom lint-tests

- //TODO: Using

whenwith enums/sealed classes - //TODO: <

reified Type> Generics instead of <*> - //TODO: Labels for

thisand scope - //TODO: Using libraries that generate interfaces (View Binding, NavigationSafeArgs, Dagger, Apollo)

- //TODO: Using coroutines for asynchronous operations

- //TODO: Using Kotlin Gradle DSL

- //TODO: Adding static analysis tools, like Detekt